Background

Scope and Purpose

Visualizing Colonial Philadelphia is a digital exhibit that are the results of my own ruminations and research on the history of early American urban space. Philadelphia is the case study of this small exhibit because it has one of the most robust trails of documentation surrounding the planning, construction and occupation of the city; a pile of riches for this type of project.

This digital project constructs a narrative around how early historians can investigate early colonial spaces using the computational tools of the twenty-first century. I have constructed it in a way that is attainable for the audience to comprehend and follow the educational process I went through to understand colonial urbanization. As a result of uncovering this history, I realized another story told by this exhibit: how twenty-first century computational tools extract new data from physicals maps. Hopefully others can use this project to jump-start their own analysis of early colonial cities, which is why I have included a rich methodology section that lays out the process and data used to build this exhibit. I want this narrative to be educational for you, the viewer, to understand what it meant to be a city in this time period and what it felt like to be urban in a very early, rural colony. But I also want it to be one puzzle piece in a larger digital history of early Atlantic cities.

A Blueprint of the Past? Understanding Colonial Maps

Often when we imagine the cities of today, we see images of skyscrapers, dense populations, immense class disparities, garbage, traffic. We also think of cities as the hubs of cultures, ethnic diversity, rich food and music scenes, museums, shopping centers. Cities, in short are places of opportunities.

In a way, early North American cities were similar to these contemporary views. They were often the only places colonists could send and receive news, buy goods, trade, listen to lectures, and interact with people from all over the world. They were also the sites of filth, destitution, and disparity, the shortcomings that have been baked into our cities of today.

But how can we “see” historical cities?

Maps are usually the answer to this question, and many historians look to maps — drawn, printed, or transcribed — to get as close as possible to visualizing history. In some ways, maps are a window into another era and a bygone space, but these historical maps, particularly those in the early American period, skewed reality with the power they held.

“Charting coastal waters and rivers, plotting towns and land grants, erasing as well as inscribing ethnic communities, drawing borders between nations and townships, American-made maps answered state and local demands for measuring the physical and social world, establishing order for some while disenfranchising many others.”

The Social Life of Maps, page 4

The initial purpose of a map, especially one used for colonial purposes, should always be considered when historians are analyzing them. As noted in the quote above, the mapmaker (and those replicating, printing and circulating these maps) had the power to erase reality literally at their fingertips. If indigenous boundaries were not respected, then they were not drawn. Land plots occupied by the enslaved? Probably left unnamed or were excised from the final product. Maps hold so much data and history that their use as both documents and as historical objects are equally important when used digitally.

Methodology

Process

This project stemmed from my interest to better understand early colonial urban space and the access to research funding through the DH fellowship at the American Philosophical Society. The COVID-19 pandemic dramatically effected my ability to complete all aspect of this project, and thus it is a pared down version of the exhibit I wanted to create.

Much of this project was using digital tools to analyze early colonial spatial materials. I spent time studying the architectural history of early Philadelphian buildings, mainly rowhouses and their blueprints. I also studied the maps, surveys, and prints of early Philadelphia to help understand its change over time.

Computational Programs

This project was made using SketchUp Pro 2019, Unity 2019 2.21, and ArcGIS Pro. The exhibit was created using ArcGIS StoryMaps.

Access to the SketchUp Files for the buildings I made to visualize early Philadelphia in 3D can be found below. Blueprints from Elfreth’s Alley and other colonial buildings were used to build simplified replicas.

3D Models

Time was spent researching the architecture of colonial Philadelphia, particularly the dimensions of the buildings that were later 3D modelled. While much of Old City, Philadelphia is a living history of the early Republic, the architectural dimensions and details about colonial infrastructures in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries are not centralized or provide incomplete information about the structures. Much of the work put into modelling the buildings was done by educated guesswork and paring back the fine details on the buildings to make completion manageable. See below for screenshots of what the process looked like as I modelled the buildings.

Access the SketchUp files for the below buildings. These are simplified buildings made using blueprints and data about colonial rowhouses. Personal changes were made, and these buildings should not be used as exact models in any way.

- Single room rowhouse

- Single room rowhouse – 3 floors

- London-style rowhouse (roughly based on the façade of Powel House)

VR Experience

After the buildings were created in Sketchup Pro, the models were imported into Unity for VR analysis. Placement, alignment and manipulation of the buildings were done in Unity, and textures were added to the surfaces. Various textures of brick, wood and stone were applied to the surfaces of the buildings, which can be very tedious and time consuming.

The VR aspect of this project is currently on pause, but the hope is to replicate a street from eighteenth century Philadelphia using the buildings and textures I have created from the first iteration of this project.

Research Questions and Analysis

The 3D/ VR part of this digital exhibit was largely impacted by the travel and social restrictions that resulted from the COVI-D19 pandemic. Instead of recreating Philadelphia’s colonial market Street, the project as it stands in the spring of 2021 has the buildings and general layout of a street corner of colonial Philadelphia. However, the process of using SketchUp Pro and Unity to analyze colonial Philadelphia has led me to wonder more about urbanization of the colonial city.

Using 3D tools to being investigating historical spaces has been discussed in recent journal articles as a step in the direction of deeper and more interdisciplinary understanding of places of the past. As these tools become more accessible in academic settings, they can allow for scholastic research that is not far from the traditional research historians conduct outside of the digital sphere.

With VCP, my process of studying historical materials using newer computational tools has led me to ask further historical questions about early colonial urbanization. I have observed how “rural” much of the Philadelphia region was in the late eighteenth century. But how did its landscape, as a densely-populated region that was largely under construction and abutted by fields and farmland, influence historical events? Did its existence as both straddling bustling city and green town effect the social and cultural makeup of its space? Did inhabitants and visitors use the spaces of Philadelphia differently than in cities like New York, Charleston, or Boston? What does the existence of Philadelphia say about the history of suburbs on the east coast? Does its pre-revolutionary history have any sway on how future cities or regions were constructed?

All of these questions branch from my ability to use computational tools to dig into the spatial history of colonial Philadelphia. I think they give historians a more intimate view of what early cities were like before mass urbanization in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Just from the preliminary work done to visualize early Philadelphia uncovers the prospects of what 3D/VR tools can do to strengthen historical inquiry.

Sources

American Philosophical Society; Nebiolo, Molly E.; and Heider, Cynthia, “Quit Rent Rolls in Philadelphia County (Penn Family Estates), Due 1688/9,” 03/01/20 – 06/01/20. 43. Philadelphia, PA: McNeil Center for Early American Studies [distributor], 2020. https://repository.upenn.edu

Hamilton, Alexander, Carl Bridenbaugh, Gentleman’s Progress: the Itinerarium of Dr. Alexander Hamilton, 1744; Ed. With an Introd. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1948. Access through Hathi Trust Digital Library.

Licastro, Amanda, Angel Nieves, Victoria Szabo, “The Potential of Extended Reality: Teaching and Learning in Digital Spaces,” Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy, Issue 17, May 2020.

Support

This project would not have come to fruition without the support of the American Philosophical Society and the NULab for Texts, Maps, and Networks. I would especially like to thank the Center for Digital Scholarship at the APS and Jessica Linker for their feedback, support, and knowledge as the project has evolved.

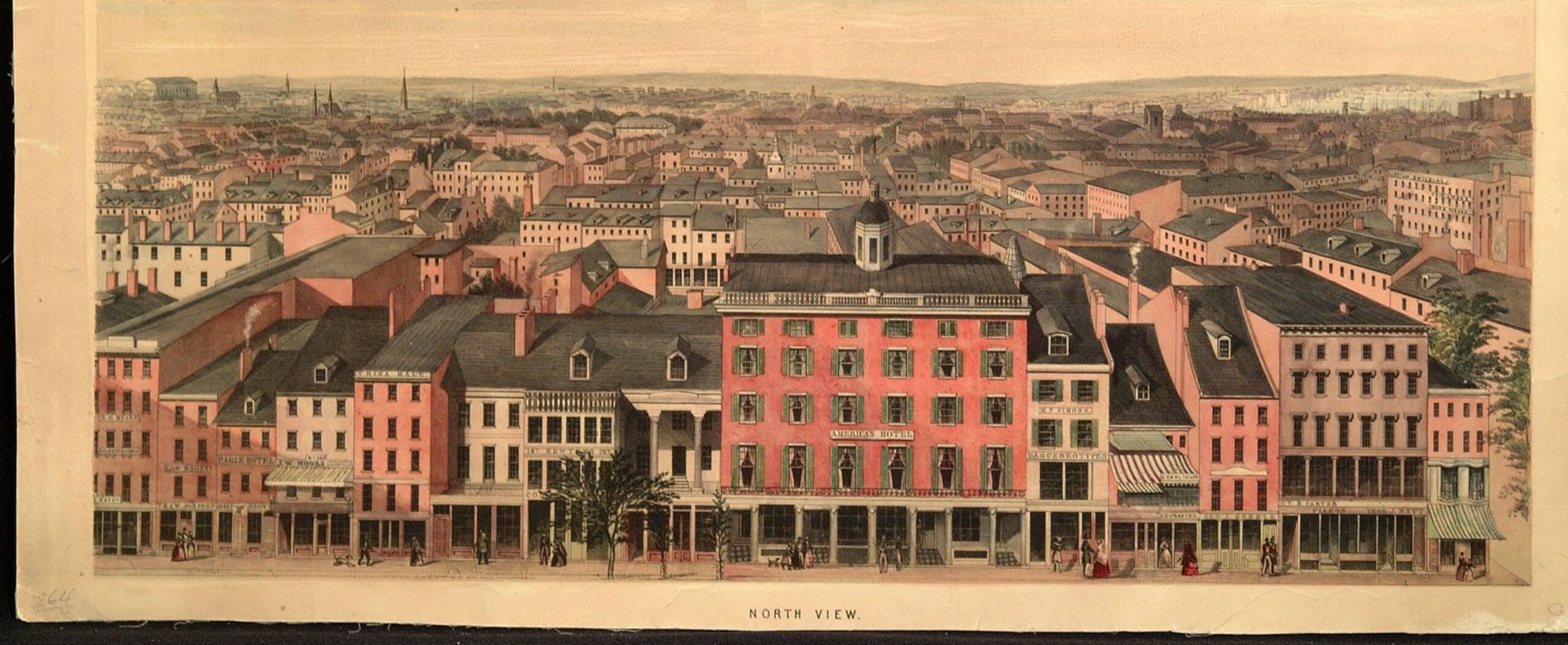

Header image: North view of Philadelphia by Edwin Whitefield, n.d. Courtesy of the American Philosophical Society.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.